features

‘Red Light’ business: The tax man’s onslaught

•Mixed reactions greet government’s plan to tax oldest profession

•You can’t criminalise vocation, yet subject it to tax- ‘runs girls’ fire back

It is a profession as old as civilisation, yet perpetually lurking in the shadows of the law. A covert agreement on social media; a secret bargain at a club; a trade of pleasure for financial benefit! In Nigeria, they are colloquially known as “runs girls-” a moniker that succinctly captures the transient, mission-based nature of their work. Their economy is vast, informal and largely untaxed—a parallel financial universe where billions of Naira exchange hands, unseen by the government’s revenue radar. But now, the walls between this shadow economy and the state are being torn down, not by morality police, but by the taxman.

The tax reform policy has been a debate that remained on the front burners of national discourse for obvious reasons. For the government, it is a policy that will bring in more revenue into its coffers; for the payee, it is one that will take out more money from his pocket.

However, the government, since its tax policy pronouncement, has embarked on a huge enlightenment campaign to sell the benefits in the reform policy to the public. In doing this, and owing to the quantum of the tax “business” he now superintends, the Chairman of the Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms, Taiwo Oyedele, has had to talk about it constantly to get the message across. “The Acts comprehensively overhaul the Nigerian tax landscape to drive economic growth, increase revenue generation, improve the business environment and enhance effective tax administration across the different levels of government.”

Yet, the government may have also found a way of mitigating the likely burden this policy may have on her people. For instance, there is a provision for an exemption of manufacturers and farmers from paying withholding tax as a way of reducing the tax burden on businesses.

“We want to reduce the burden on businesses, promote competitiveness, equity and ease of compliance and tax avoidance, detect tax evasion and reflect what is happening globally. We are creating an exemption for withholding tax small businesses and what we have in mind is N50 million. We have reduced the rate for real businesses to as low as two per cent- people producing goods and services because the margins are very small. We have created an exemption for manufacturers- so if you are a manufacturer, don’t worry about withholding tax. If you provide input to manufacturers like farmers, don’t worry about withholding tax,” Oyedele had explained at a forum in June 2024.

But this exemption may after all have to be taken over by some other categories of workers or “producers.” Last week, Oyedele, during a tax education session in Lagos, made a pronouncement that has kept the cyber space buzzing with his declaration that from January 2026, the income of “runs girls” would be subject to taxation. His logic, delivered during a tax education session at a Lagos church, was starkly legalistic, deliberately divorced from moral judgment: “If somebody is doing runs girls, right, they go and look for men to sleep with, you know that’s a service, they will pay tax on it. One thing about the tax law is it does not separate between whether what you are doing is legitimate or not. It just asks you whether you have an income.”

This announcement is a single, provocative thread in the “over 400 pages” of what Oyedele calls “the most transformative, most significant tax reforms in our nation’s history.” Yet, it has become the defining image of the new policy for many, a proverbial elephant that the public has latched onto.

A “runs girl” is generally described as a woman, either single or married, who engages in relationships with multiple men for financial benefit. While some criticise this lifestyle as promiscuous, others see “run girls” as resilient figures, adapting to economic challenges in their own way.

Burgeoning “runs girl” industry

Curiously, the position of the tax man may have remained flabbergasting to several Nigerians, sparking discussions across the divide. But, a research survey conducted and circulated across the cyber space, may have given the government an idea of the “economic prosperity” hidden away in the business- hence, its interest of getting its revenue cut from the commercial sex industry in the country.

A 2024 survey, widely circulated on social media, attempted to quantify this behemoth in Lagos State alone. The figures are nothing short of astronomical. The survey estimated that in 2024, men in Lagos spent a staggering N661billion to satisfy their sexual urges with commercial sex workers. Of this, N329 billion was paid directly to the women for their services, while the remaining N332 billion was spent on associated costs: lavish dinners, hotel rooms, gifts, drugs, and sexual enhancers. To put this in perspective, the proposed 2024 budget for the entire Nigerian Ministry of Health was roughly N1.1 trillion. The “runs girls” economy in a single state is a significant fraction of the nation’s health budget.

A further breakdown of the demographics and economics of these revealed that of the 3.1 million sexually active men in Lagos, 1.86 million engaged in transactional sex. The average fee charged was N36,750, with premiums in affluent areas like Eti-Osa , encompassing Ikoyi and Victoria Island) reaching as high as N100,000 per transaction.

Crucially, the survey illuminated the profound economic ripple effect of this income, demonstrating that the N329 billion earned was not hoarded but actively and immediately injected back into the formal and informal economies. A significant portion, N93 billion, was cycled into the beauty and pharmaceutical sectors through spending on body and skin maintenance products. Furthermore, the industry served as a crucial source of financial support for extended families, with N62.5 billion sent home to relatives, while another N62.5 billion fueled commerce in clothing, accessories, real estate through rent, and the transportation industry. A surprisingly substantial N46 billion was directed into investments and speculative ventures like cryptocurrency, forex, and trading, highlighting a segment of workers actively seeking to build capital. Finally, underscoring their expenditure on personal well-being and advancement, N15 billion each was allocated to healthcare—covering antibiotics, supplements, and STD treatments—and education, for university programmes and other coursework.

This data paints a picture not of isolated, clandestine acts, but of a vibrant, high-value economic sector with deep interconnections to the mainstream economy. For a government struggling with revenue generation, this N329 billion pool of untaxed income represents a tantalising, if incredibly complex, prize.

Voices from the shadows

But Oyedele’s position on taxing “runs girl” has been met with a mixture of disbelief, anger, and cynical amusement by the women it targets. For instance, a 24-year-old runs girl who operates in high-end hotels in Abuja, Amara (not real name), laughed hysterically when told about the policy.

“Tax? On what? The money I use to treat my body and feed my family? Let me ask you, how will the taxman know how much I make? Will he be there in the hotel room to count the cash? Or will my ‘clients’ now ask for a receipt? This is just another way for them to harass poor people. The police are already collecting their own ‘tax’ by arresting us and demanding bail money. Now the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) wants its own share. They should go and tax the politicians first.”

Jennifer, a tertiary institution student in Lagos who says she engages in “runs” to pay her tuition and support her younger siblings, expressed a more nuanced fear. “It’s not funny. They are saying this because they see us as easy targets. We are already stigmatised. If we try to comply, how do we do it? Do I walk into a tax office and say: ‘Hello, I am a prostitute, here is my tax’? They will arrest me on the spot. Or they will use the records to blackmail us. This policy is not well thought out. It’s like they want to drive us deeper into hiding.”

For Bimpe, a single mother of two in her 30s working the streets of Ikeja, the issue is one of basic survival. “My profit is what is left after I pay for my room, food, and my children’s school fees. There is no profit most months. If they take tax from the little I have, how will I survive? The government does nothing for me. No light, no good water, no security. Now they want to take from the little I hustle for with my own body. It is not fair.”

Nigeria is not the first country to grapple with the conundrum of taxing sex work, a challenge that forces a government to define its stance on legality, labour and legitimacy. The relationship between sex work and the state can be distilled into a single, powerful transaction: the payment of tax. This exchange, or its absence, reveals whether a government views the worker as a criminal, a citizen, or something in between, creating a global patchwork of contradiction and obligation.

In Europe, the model is one of pragmatic integration. Germany’s foundational Act to Regulate the Legal Situation of Prostitutes (ProstG) of 2002 formally recognises sex workers as self-employed individuals. This status, governed by standard German tax law (EStG §4 & §), requires them to register a business, obtain a tax number, and file annual returns, allowing deductions for everything from professional attire to workplace rent. This framework grants access to social security and pensions, weaving the trade into the formal economy. A widely cited 2009 report by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) estimated the sector’s total economic contribution at over €6 billion annually, a significant portion of which was taxable, despite ongoing challenges with full compliance.

Similarly, the Netherlands’ Lifting of the Brothel Ban Act (2000) allows workers in Amsterdam’s famed Red Light District to operate as independent entrepreneurs, leasing windows from the city and paying income tax. The goal is transparency, yet as reports from the Dutch Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) consistently document, the incentive to operate in the cash-based informal economy remains a persistent hurdle.

Moving beyond Europe, Australia offers a blueprint of assertive administrative oversight. In states where the trade is decriminalised, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) leaves no room for ambiguity. Its ruling TR 2023/1 explicitly states that income from prostitution is assessable and must be declared, with clear guidelines on deductible expenses. Crucially, the ATO actively enforces this, using data-matching technology under its “Online entertainment industry data-matching programme” to cross-reference escort website advertisements with tax returns, ensuring this recognised business pays its share.

In stark contrast stands the United States, where a deep philosophical paradox prevails. Prostitution is largely illegal, yet the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) mandates in its Publication 17 that all illegal income, including from sex work, is taxable. This principle was cemented by the 1927 Supreme Court case: United States v. Sullivan, which ruled that the Fifth Amendment does not excuse filing a tax return. The state effectively demands its share while denying the work’s legality, creating a catch-22 where compliance is virtually zero.

This American contradiction highlights a critical question for the Nigerian context: what happens in regions where the very concept of a “red light tax” is unthinkable under the law? The broader African context provides a clear, sobering answer. No African nation has a formal system to tax sex workers as a legal profession. Instead, the continent showcases a spectrum of state interactions defined by exclusion and coercion, a reality Nigerians know all too well.

In countries like Kenya and Nigeria, where criminalisation is the norm, a perverse form of informal “taxation” thrives. As documented in an Amnesty International Report (2020) on Kenya and a Human Rights Watch Report (2022) on Nigeria, police systematically extort bribes from sex workers, creating a corrupt levy that funds predation, not public services.

Senegal presents a unique, health-focused exception. Its legal framework allows regulated prostitution, requiring health cards and confining work to licensed brothels. However, analyses by the International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe (ICRSE) and the International Alliance of Women (IAW) confirm this is a model of regulation, not fiscal integration; the state monitors bodies, but does not formally tax their income.

Most telling is South Africa’s landmark stance. In a historic move for rights-based policy, the 2023 Draft Sex Work Bill includes a clause (Section 17) that explicitly prohibits the South African Revenue Service (SARS) from taxing a sex worker’s income until the profession is fully decriminalised. It is a powerful statement of principle: no taxation without representation and protection.

Between pragmatism and peril

Economists, legal experts and social commentators in the country are divided on the feasibility and ethics of the proposal. A Lagos-based public finance economist, Dr. Oluwaseun Adebayo, sees logic in the move.

“From a purely economic standpoint, the principle of horizontal equity in taxation demands that all income, regardless of source, should be taxed equally. This massive informal economy distorts the market and deprives the state of crucial revenue that could be used for public goods. The N329 billion figure, if even half of it is taxable, represents a significant revenue stream. The intent to broaden the tax base is correct. However, the ‘how’ is a nightmare. Without decriminalisation or a specific legal framework that protects these women and provides a clear mechanism for compliance, this is more of a philosophical statement than a practical policy.”

For the Founder and General Overseer of Calvary Bible Church, Dr. Olumide Emmanuel, the issue remains a paradox exposing the nation’s contradictions as “the most religious nation on earth” and at the same time “the most corrupt, and the poorest.”

Dr. Emmanuel, who is also a wealth creation coach, acknowledged that N661 billion revenue generation in the “runs girl” sector alone in Lagos state, if true, shows the economic reality and prosperity in the “sector.” “That is obviously an industry; anything that is producing that kind of money is an industry you should put your eye into.”

He however said there is a need to draw the line of distinction between business and morality, given the sensitivity and wider implications on societal values. “There is a difference between legality and morality. We need to understand that. Everybody that is earning an income must be taxed. So legally, yeah, if you make income, you should be taxed. There’s nothing legally wrong in that.”

“But morally, what that now means is that we are legalising prostitution from the back door. It means that if I pay tax to you, then you cannot now come to me to say that the money I paid you, the source of the money is wrong. So, legally, it’s not wrong. You get income, you must be taxed. Morally, it’s disgusting,” he concluded.

Yet, a human rights lawyer, Barrister Paul Mgbeoma, is concerned about the legal and safety implications.

“Mr. Oyedele’s statement, while legally accurate in a narrow sense, is dangerously simplistic. It ignores the fact that these women are operating in a criminalised environment. Forcing them to declare their income for tax purposes is essentially asking them to self-incriminate. It could provide a new tool for law enforcement to extort and abuse them. The state cannot have it both ways. It cannot criminalise an activity on one hand and demand its fair share of the profits on the other. The first step must be a national conversation about decriminalisation or legalisation, to ensure the safety and rights of the workers, after which taxation becomes a straightforward administrative process.”

Still, Pastor Best Ezeani of the Redeem Christian Church of God offers a moral and religious perspective.

“As a man of God, I must state unequivocally that the church condemns sin in all its forms, and prostitution is a sin. However, the role of the government is governance, not morality. While we preach repentance and a change of life to these women, the government has a duty to manage the state’s finances. If the law says all income is taxable, then so be it. Perhaps this could even serve as a deterrent. But the government must be careful not to appear to be endorsing or profiting from sin. The focus should be on creating legitimate jobs and fostering moral rearmament.”

An Islamic Scholar in Lagos, Imam Sani Abdulaziz, shares a similar moral concern. “In Islam, this profession is strictly forbidden (Haram). To now formalise it through taxation is deeply troubling. It gives it a semblance of legitimacy that is against our religious tenets. The government should be focusing on empowering youth and women through halal means and strengthening family values, not finding ways to tax immoral earnings.”

The Challenge

The chasm between Oyedele’s legal pronouncement and its practical execution is vast, raising the critical question of how the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) could possibly operationalise this policy. The first and most fundamental hurdle, according to Mgbeoma is assessment and declaration: “Would sex workers be expected to formally file annual tax returns, declaring their gross income and then itemising deductible business expenses such as condoms, outfits, and hotel costs?”

This scenario, he said, seems fanciful, if not entirely absurd, within a context defined by widespread social stigma and active criminalisation of their profession.

“Enforcement presents another monumental challenge; the notion of FIRS tax auditors being deployed to brothels and nightclubs is not only logistically implausible but also risks catastrophic clashes with law enforcement and would inevitably create new, vicious forms of extortion. Furthermore, while a small segment of high-end workers may leave a digital trail through online advertising and bank transfers, the overwhelming majority of transactions are conducted in untraceable cash, making any systematic tracking of income nearly impossible.

“Finally, the alternative of shifting the tax burden to the clients—treating them as withholding agents—would be equally unenforceable and absurd, completing a picture of a policy that is conceptually straightforward but practically a minefield,” he added.

Oyedele himself has urged Nigerians not to focus solely on this one issue, comparing it to the parable of the blind men and the elephant. He emphasises the broader, progressive goals of the reform: simplifying the tax system, exempting low-income earners and ending multiple taxations. Yet, it is this very “runs girl” comment that has captured the public imagination, symbolising the reform’s ambitious attempt to drag the entire informal economy into the tax net.

Reflections

A public policy analyst, Mayowa Sodipo, may have summed up the diverse submissions of stakeholders’ views, especially the “paradoxical” position submission of Dr. Emmanuel. He argued that contemplating taxing “runs girls” is a stark reflection of the country’s enduring contradictions- a deeply religious society with a sprawling informal economy; a state with ambitious revenue targets but weak institutional capacity; a legal system that criminalises an activity whose economic contribution it now seeks to harness.

For the women like Amara, Jennifer and Bimpe, the taxman’s announcement is just another potential predator in a landscape already filled with danger. It underscores their precarious position—exploited by clients, harassed by police, judged by society, and now pursued by the treasury, all while being denied the basic protections and recognition afforded other workers.

The path forward is fraught. The German model of legalisation and regulation, according to experts, offers a pragmatic blueprint for successful taxation but would require a seismic shift in Nigeria’s social and legal fabric. As the nation grapples with this controversial proposal, the story of the “runs girl” and the taxman has become a powerful allegory for the country’s struggle to reconcile its morals with its money.

Business

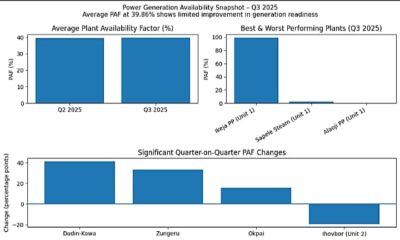

The unending meter conundrum

The federal government has implemented several initiatives aimed at ensuring adequacy in electricity metering. These efforts have however proved to be almost ineffective even as the metering gap in the country remains at seven million. Stakeholders in the industry have since called for the liberalisation of meters sales and purchase as a way around the conundrum. Last week, the Power Minister appeared to have stirred the hornet’s nest declaring that meters under DISREP be issued and installed free of charge to consumers. The fallout has caused bickering between the DISCOS, consumers and other stakeholders- threatening over the installation of 1.5 million meters.

The Power Minister, Adebayo Adelabu, may have been a self-effacing man during his time at the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). However, owing to the quantum of demands and expectations of the ministry he superintends presently, the Adelabu has had to shout himself to the rooftops.

While the minister may have unwittingly been vocal, stakeholders are convinced that it may be as a result of the need to succeed by delivering power to the Nigerian public, especially at a time when patience seem to be running out.

His latest outburst on metering is one that obviously touches the raw nerves of electricity consumers as well as the utilities.

“I want to mention that it is unprecedented that these meters are to be installed and distributed to consumers free of charge—free of charge! Nobody should collect money from any consumer. It is an illegality. It is an offence for the officials of distribution companies across Nigeria to request a dime before installation; even the indirect installers cannot ask consumers for a dime. It has to be installed free of charge so that billings and collections will improve for the sector,” an elated Adelabu said last week during an on-site inspection of newly imported smart meters at APM Terminals, Apapa, Lagos.

But the statement by the Minister exposed a brewing tension in the sector, leading to divergent tunes from all stakeholders in the electricity value chain, placing the Distribution Companies (DisCos) and the Federal Government at logger heads over who pays for the cost of the meters and installation.

The metering schemes

The issue of meters in the sector remains very touchy given that efforts at ensuring adequately metering of electricity consumers have at best not yielded the desired result. To date, Nigeria has an estimated shortfall of seven million meters- a situation that has both placed a huge revenue loss on the electricity value chain as well as the consumers who are slammed bith bogus estimated billings.

There are various metering schemes initiatives by the federal government aimed at reducing the seven million metering gap in the country. These include Meter Asset Provider (MAP), as enshrined in 2018/2019 via a NERC regulation allowing third-party investors to supply and install meters. Customers under this scheme pay upfront for meters and are refunded through energy tokens over time. MAPs are companies granted approval by NERC to procure and install meters for customers of DisCos. Customers are required to make an upfront payment for the meter and the cost recovered over a period of time approved by the NERC.

In 2020, the National Mass Metering Programme (NMMP), a Federal Government initiative funded by the CBN to provide free meters to Nigerians, aiming to end estimated billing, was introduced. This intervention sought to increase metering rate, eliminate arbitrary estimated billing, strengthen the local meter manufacturing sector, job creation and reduction of collections losses. Under this scheme, meters are provided and installed at no upfront cost to the consumer.

A seed capital of ₦200 billion was invested to facilitate the Nigeria Electricity Supply Industry (NESI) revenue collections through the programme. Under Phase-0 of the NMMP, the sum of ₦59.280 billion was set aside for financing the installation of one million meters.

From inception to date, 89.96 per cent of the funds allocated for NMMP under phase 0 has been disbursed to 11 DisCos for procurement of 962,832 meters through 23 Meter Asset Providers.

The funding under Phase 0 is through the CBN/NESI; financing for the phase 1, with a procurement of 1.5 million meter units, is through the CBN/ DMBs (Deposit Money Banks), while financing for the Phase 2, with a four million meter units procurement, is from the World Bank.

Still is the Presidential Metering Initiative (PMI), established in 2023, as a five-year, 10-million-meter initiative, supported by the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) and World Bank, designed to fast-track metering. This initiative aims to close the metering gap for 60 per cent of estimated-billing customers by 2027 through the deployment of over five million smart meters to be funded by the Meter Acquisition Fund (MAF) and Federation-funded initiatives. The Meter Acquisition Fund (MAF) Tranche B, guaranteed NERC-approved funds of ₦28 billion for Discos to provide free meters specifically for Band A and B customers.

Dr. Joy Ogaji

Funding for meters under MAF is built from a pool of contributions from all 12 DisCos based on their market collections. It gives priority in tiers- with the current phase (Tranche B) focusing on completing the metering of all outstanding Band A customers before fully extending to Band B. DisCos must use these funds to procure meters through competitive bidding and complete installations by specific deadlines.

Also is the Distribution Sector Recovery Program (DISREP), a $500 million World Bank-funded initiative to deliver 3.4 million smart meters for free to consumers. It also aims to improve the financial and technical performance of the country’s electricity distribution companies (DisCos). Like the NMMP and MAP Schemes, DisCos are expected to repay the cost of these meters over a period of ten-years. DisCos are also responsible for distribution, installation and maintenance of these meters within their franchise states.

A far older metering scheme was the Credited Advance Payment for Metering Implementation (CAPMI), introduced by the NERC in 2013. The CAPMI allowed electricity customers to pay for their own meters to speed up installation and avoid estimated billing. Customers, who paid for meters directly were to be refunded through energy credits over a set period. The scheme was wound down in 2016 after it was found that only about 500,000 meters were deployed between 2013 and 2016, with many DisCos failing to fulfill their obligations despite receiving funds.

How free are meters?

Adelabu’s free meter installation directed that prepaid meters procured under the World Bank–funded DISREP, has elicited mixed reactions. While the government argued that electricity consumers will only pay for the ongoing free meter installation through deductions from their electricity tokens, the DisCos are concerned over the long period of recovery of such funds which spans over a period of 10 years. They argue that such arrangement has effects on their operations, especially cost recovery, installation expenses and the financial implications.

The position of government is understandable given that suppliers, it claimed, have already been fully paid for both the meters and the installation. Therefore, the reasoning is that Discos charging consumers again for installation would not only slow down the meter uptake, but it will also undermine the goal of the initiative.

The Minister’s team pointed to poor enumeration and inaccurate customer information as the main bottlenecks, disclosing that installers are often sent to wrong addresses or to premises that are not technically ready for metering. The Director-General, Bureau of Public Enterprises (BPE), Ayo Gbeleyi, takes the Discos’ position with a pinch of salt. Gbeleyi, who was in attendance at the N501billion bond issuance signing ceremony to settle legacy debts in the power sector, regretted that the god gesture of government in line with free metering was being antagonised by the utilities.

He maintained that claims of repayment over 10 years assertions were inaccurate and misleading, explaining that cost of meters, transformer, feeders, and other components of investments, are embedded in tariffs and recouped over time.

“We’ve had pushback. The truth is, every component of investment that goes into the DisCos gets recouped through the tariff structure. So, whether it is a feeder pillar, whether it is a transformer, or whether it is a meter, we as consumers will ultimately pay for those pieces of equipment through the tariff design,” the BPE boss clarified.

He explained further: “What they (Discos) are not telling you is that the Federal Government’s major intervention is indeed one of the best loan transactions today extended to the power sector. It is a 20-year loan facility. It comes with a five-year principal moratorium and a two-year interest moratorium to the DisCos. We have never seen any capital lending to that sector of that magnitude in the history of the power sector in Nigeria.”

A public sector analyst, Mayowa Sodipo, corroborated the position of Gbeleyi, insisting that at no point in time was meter allocation ever free of charge. For him, the while Adelabu may have played to the gallery with his statement knowing that these meters and installation costs have been factored into the electricity tariff paid by the consumer, he may have equally saved the consumers from exploitation.

“At no point was meter ever free to any consumer. You pay through your electricity purchase because it is deducted from your token over a period of time. So the Discos are not the ones even paying for the meters as they are now trying to claim, but the consumers because the cost is deducted from their electricity tariff bought. So the Discos are not paying but the consumers are paying for the meters,” Sodipo argued.

But the Discos are worried that as a business concern, the burden on payment for meters still rests with them. An official of a South West Disco who spoke on condition of anonymity depriving payment for installation is an extra burden on the Discos because this segment is contracted out to installers, who are not on the pay roll of the Discos.

“So if consumers are not paying for installation, who should? Is the minster saying that the Discos should still carrying the financial implication of this?” the official asked rhetorically.

In a submission on the development, a Kano state based social commentator, Dr. Abubakar Ibrahim, for Nigeria to close its metering gap, there is need for collaborative policy implementation between the regulators, government authorities, Discos and meter providers and installers.

“They must all agree to work together to establish a clear and sustainable funding framework that covers both meter procurement and installation. The federal government on its part must design a financial framework that will balance customers’ interest with the sector financial sustainability,” Dr. Ibrahim said.

He further said that while the federal government’s objectives is clearly to close the metering gap and ensure fair billing, however, lack of alignment with DisCos could unintentionally delay the very benefits the policy seeks to deliver.

The Executive Director, Emmanuel Egbigah Foundation, Prof Wunmi Iledare, submission in in sync with Dr. Ibrahim’s. He insisted that the development is a symptom of deeper structural and governance failures in the power sector. He said it is appalling for the Federal Government, as a part-owner of the DisCos, to publicly complain about their conduct without addressing underlying regulatory lapses, leaves more to be desired.

Way to go

Dr. Ibrahim and Prof. Iledare’s submissions summarises a critical issue in the metering scheme. Key industry stakeholders in the value chain blamed the Discos shows of apathy of Discos towards meter installation on the fact that they have not been part of the procurement process including the selection of installaters.

“For this DISREP, the federal government nominated the installers, at a low cost expecting DisCos to cover some part of the cost to mobilise the installation activities. As usual since DisCos are not part of the entire procurement and acquisition process unlike other metering mechanisms, then they will show apathy; DisCos always wanted to have a say in some of these projects.

“On paper the paper the meters are free but the last mile issues are cost burdens that the DisCos are not willing to cover. This is why the process is slow and bulk of the facilities are in stores across the DisCos,” a very senior official of a Disco, who asked to be anonymous owing to the sensitivity of the matter, revealed at the weekend.

With a recurring situation, the Managing Director / CEO/ Executive Secretary, Association of Power Generation Companies (APGC), Dr. Joy Ogaji, advocates that metering should be liberalized. To this end, Ogaji argued, both government and Discos should hands off meter matters and allow it to run like the mobile phone is run in the telecommunications sector so that consumers can freely go to the open market to buy meters.

Although she agreed that when customers buy meters from shops instead of DisCos, revenue assurance can become challenging, she nonetheless said this can be addressed through meter registration with DisCos to track usage and ownership; standardistion, by mandating the use of approved, tamper-evident meters with remote monitoring capabilities; implementing a centralised vending systems for meter top-ups, linking purchases to customer accounts and collaboration with shops and regulators to ensure compliance with industry standards, insisting that this approach helps DisCos track revenue and reduce losses

“Design the standard or specifications for the meters for various categories- 1-phase, 3phase etc; make it available in shops for anyone to purchase; train installers and only contact your Discos to inform them of synchronization. With this, no cunnundrum; everyone is happy, except there are ulterior motives,” Ogaji submitted, warning that if after 15 years of privatization of the sector, metering still remains a problem, then there is no point continuing with is the way it is being done.

features

How policy gaps keep Nigeria dependent on petrol imports

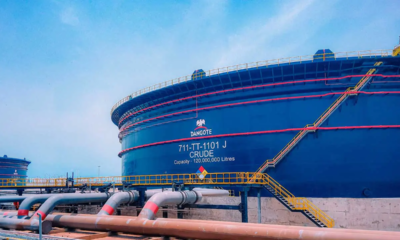

Nigeria’s persistent dependence on imported petrol has become one of the most expensive contradictions in its energy economy. Despite vast crude oil reserves and growing domestic refining capacity, billions of dollars continue to flow abroad each year, draining public finances and foreign exchange. This paradox has intensified scrutiny of regulators and policymakers, with stakeholders demanding decisive reforms that prioritise local refining, restore competitiveness, and finally break the cycle of import dependency.

The call on the country’s newly appointed petroleum sector regulators to make domestic refining and crude oil production top priorities is well founded. For several years, petrol importation has remained a major drain on public finances, costing the government an estimated $18 billion over the past five years alone.

In setting expectations for the new appointees, stakeholders across the oil and gas industry have been unequivocal in their demand that this trend be reversed, warning that it has become a cankerworm eating deep into the economy. The Chief Executive Officer of the Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise, Dr. Muda Yusuf, was particularly forthright, cautioning that failure to decisively address the issue would further entrench Nigeria’s dependence on fuel imports and deepen its economic vulnerabilities. He urged both the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) and the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) to pursue policies that reduce import reliance, expand domestic capacity, and attract sustained investment into the oil and gas sector.

According to Yusuf, strong and deliberate support for domestic refining must be treated as an immediate and non-negotiable priority in the downstream segment. He argued that government policy should clearly favour locally refined petroleum products through targeted fiscal, regulatory, and infrastructural incentives for both public and private refineries, while actively encouraging new investments in refining capacity. “Nigeria must end the current distortion whereby imported petroleum products are made to compete with locally refined products under unequal regulatory and fiscal conditions. This does not constitute fair competition. Genuine competition only exists when all operators function within the same policy, tax, and regulatory environment,” he noted.

Yusuf stressed that the argument goes beyond investor protection to the heart of Nigeria’s long-term economic interests. A strong domestic refining base, he said, is fundamental to building a resilient, energy-secure, and economically sovereign nation. It is also critical for job creation, foreign exchange conservation, macroeconomic stability, and the development of export-oriented refining capacity. More importantly, he described domestic refining as a key pathway to backward integration and resource-based industrialisation. By strengthening refineries, Nigeria also reinforces its petrochemical, fertiliser and allied industries, creating broader industrial value chains capable of driving inclusive and sustainable growth.

These submissions are reinforced by public affairs analyst Mayowa Sodipo, who described it as a “paradox” that Nigeria continues to export crude oil while importing refined petrol. This anomaly, he noted, was precisely what the Dangote Refinery was designed to address by boosting local output and conserving foreign exchange. While he acknowledged that the cost of petrol imports places immense pressure on the country’s foreign reserves, Sodipo also observed that prevailing market realities can, at times, make fuel imports unavoidable. “Although policies such as the Petroleum Industry Act are intended to promote local refining, significant challenges remain in implementation, transparency, and in balancing incentives for domestic production with the demands of market competition,” he said.

The rising burden of fuel imports

For several years, the cost of petrol importation has remained a major drain on Nigeria’s resources, particularly its foreign exchange. In the first half of 2025 alone, petrol imports cost the country about N4 trillion, with an additional N1.28 trillion recorded in the third quarter of the year. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) show that Nigeria imported N1.76 trillion worth of petrol in the first quarter of 2025. This figure rose sharply to N2.3 trillion in the second quarter, before moderating to N1.28 trillion in the third quarter, bringing total petrol import spending for the first nine months of the year to N5.28 trillion. Figures for the fourth quarter are yet to be released.

A review of petrol import expenditure over the past four years reveals a persistent and escalating trend. In 2020, Nigeria spent N2.01 trillion on fuel imports. By 2021, this figure had more than doubled, rising by 126.9 per cent to N4.56 trillion amid growing import dependence and global price volatility. The upward trajectory continued in 2022, with costs surging by 69.1 per cent to N7.71 trillion, driven largely by higher international crude prices. Although petrol import spending dipped marginally by 2.6 per cent to N7.51 trillion in 2023, the reprieve was short-lived. In 2024, the figure spiked dramatically by 105.3 per cent to N15.42 trillion—the highest on record—largely reflecting the sharp depreciation of the naira against the US dollar.

Economists argue that this sustained reliance on petrol imports has continued to undermine the domestic economy. Beyond the pressure it places on foreign exchange reserves, import dependence effectively exports jobs, supporting employment in refining countries while stifling opportunities within Nigeria. This concern is reinforced by an analysis conducted by Statisense, an AI-driven data analytics firm specialising in financial report analysis. The study revealed that in 2023, Nigeria spent approximately $18.7 billion importing petroleum products, including premium motor spirit (PMS), from about 20 countries, several of them within Africa. From just eight African countries, Nigeria spent an estimated $243 million on petroleum imports.

The data further highlight striking trade imbalances. Petroleum imports from Malta alone surged by $2.03 billion to $2.08 billion in 2023, compared with just $47.5 million in 2013. NBS data show that in the third quarter of 2023, Malta ranked among Nigeria’s top five import sources. During that period, Nigeria imported goods worth $561.37 billion from Malta, with petroleum products accounting for roughly one-third of total imports. Overall, petroleum imports were valued at about $36 trillion in 2023, with petrol accounting for approximately 21 per cent of total imports.

However, figures from Trade Map, an online trade statistics database managed by the International Trade Centre (ITC)—a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation—present a slightly different picture of import origins. According to the platform, Nigeria’s largest petrol imports in 2023 came from Togo, valued at $109.3 million, and Tunisia, at $104.35 million. Taken together, these statistics underscore Nigeria’s continued dependence on imported fuel, despite ongoing efforts to expand local refining capacity. Analysts attribute this persistence to a combination of supply chain inefficiencies, demand–supply mismatches, and delays in refinery ramp-up, all of which continue to constrain the transition to self-sufficiency.

Why the preference for importation persists

Stakeholders in the oil and gas sector argue that Nigeria’s continued preference for petrol importation is rooted in decades of underinvestment, operational inefficiencies, and policy inconsistency within the domestic refining industry. The result has been chronically low local output, compounded by a persistent foreign exchange crisis that, at times, makes imported fuel appear more competitive—even with the entry of the Dangote Refinery. These factors have combined to create a complex mix of market distortions, logistical constraints, and regulatory hurdles that keep the country reliant on foreign supplies, despite long-standing aspirations for self-sufficiency.

Nigeria’s state-owned refineries, in particular, have consistently underperformed due to poor maintenance regimes and obsolete technology, leaving them unable to meet national demand. In addition, fuel marketers often find it more economical or operationally convenient to source refined products from international markets, especially when domestic production costs, transportation challenges, or supply-chain inefficiencies undermine the competitiveness of locally refined fuel.

Despite these challenges, Nigeria’s refining landscape has expanded significantly in recent years. The country currently has 30 licensed modular refineries, of which five are operational and producing products such as diesel, kerosene, black oil, and naphtha. About 10 others are at various stages of completion, while the remaining have received licences to establish.

Modular refineries are compact, skid-mounted processing plants designed for rapid deployment and lower capital costs. Using simplified refining processes—primarily distillation—they produce essential fuels and offer a flexible, decentralised alternative to large conventional refineries. Their growth is intended to enhance energy security, reduce transportation costs, and bring refining capacity closer to crude oil production sites. The operational modular refineries include Waltersmith Refining and Petrochemical Company (5,000 barrels per day), Aradel Refinery (11,000 bpd), OPAC Refinery (10,000 bpd), Duport Midstream Refinery (2,500 bpd), and Edo Refinery (6,000 bpd).

On a larger scale, Nigeria’s conventional refineries form the backbone of its historical refining capacity. The Kaduna Refining and Petrochemical Company (KRPC), established in 1980 at a cost of $525 million, was designed to supply petroleum products to Northern Nigeria. Initially built with a capacity of 50,000 bpd, it was expanded in stages to reach a peak capacity of 110,000 bpd by 1986.

The Old Port Harcourt Refinery, commissioned in 1965 with a capacity of 60,000 bpd, was constructed at a cost of approximately £12 million by Shell BP. While it operated above 50 per cent capacity in its early years, output declined steadily from the 1990s. In March 2021, the Federal Government awarded its rehabilitation contract to Italy’s Tecnimont SPA. By December 2024, the Minister of State for Petroleum Resources, Senator Heineken Lokpobiri, announced the mechanical completion and flare start-up of the facility.

The New Port Harcourt Refinery, commissioned in 1985 at a cost of $850 million, added 150,000 bpd to national capacity, bringing the combined Port Harcourt refining capacity to 210,000 bpd. Similarly, the Warri Refinery and Petrochemical Company (WRPC), commissioned in 1978, is a complex conversion refinery with a nameplate capacity of 125,000 bpd. The facility includes a petrochemical plant commissioned in 1988, producing polypropylene and carbon black, and supplies markets across southern and southwestern Nigeria.

Among private operators, Waltersmith Refining and Petrochemical Company in Imo State began operations in 2020 with a capacity of 5,000 bpd and has announced plans to scale up to 50,000 bpd in the coming years. The most significant addition to Nigeria’s refining capacity is the Dangote Refinery, a 650,000-bpd integrated facility located in the Lekki Free Zone, Lagos. Built at a cost of about $20 billion, the refinery was commissioned in May 2023. Crude processing began in December 2023, with refined products supplied to domestic and international markets from May 2024.

Other notable projects include the Azikel Refinery, a 12,000-bpd modular hydro-skimming refinery under development in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, designed to process Bonny Light crude and Gbarain condensate. The Ogbele Refinery, which started operations in 2012 as a 1,000-bpd topping plant, has since expanded into an 11,000-bpd, three-train facility producing diesel, kerosene, naphtha, and fuel oil. The Edo Refinery and Petrochemical Company, owned by AIPCC Energy, operates in two phases with capacities of 1,000 bpd and 5,000 bpd, and plans a further expansion to 12,000 bpd. Additional modular refineries include Duport Midstream in Edo State, OPAC Refinery in Delta State, and the Aradel modular refinery in the Niger Delta, which produces a range of middle distillates and fuel oils.

The rehabilitation of state-owned refineries and the completion of the Dangote Refinery were widely expected to usher in an era of fuel self-sufficiency and significantly reduce Nigeria’s dependence on imported petroleum products. However, despite these developments, large volumes of refined fuel continue to be imported.

Industry experts attribute this gap between capacity and reality to persistent operational challenges, delayed ramp-up schedules, pricing dynamics, and regulatory constraints. Nonetheless, stakeholders maintain that Nigeria’s expanding refining infrastructure remains critical to achieving long-term energy security. With a growing mix of modular, conventional, and large-scale private refineries, analysts argue that Nigeria is structurally positioned to evolve into a global refining hub—capable not only of meeting domestic demand but also of supplying refined petroleum products to regional and international markets, provided policy coherence and operational efficiency are sustained.

Private investment and profitability constraints

Investor reluctance to commit capital to refining is closely linked to the industry’s narrow profit margins. Refining is a capital-intensive, high-risk business that typically delivers low margins, except during brief periods of favourable market conditions. Returns are cyclical and heavily influenced by global crude prices, exchange rates, and supply disruptions, making refining a complex and uncertain investment proposition. Africa’s richest man and President of Dangote Group, Aliko Dangote, has publicly acknowledged this reality. Speaking during a recent media tour of the Dangote Refinery, he described refining as a low-return venture compared to other global investments. “There is a very low margin as profit on refining business. In fact, if I had invested the amount spent on this refinery on Google, I would have made twice the investment. There is very little money in refining,” Dangote said.

For modular refineries—often described as a critical bridge toward energy self-sufficiency—the profitability challenge is even more pronounced. Many modular refiners are still awaiting their first crude oil allocations, despite the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited’s (NNPC Ltd.) pledge to support them as part of government efforts to boost local refining and reduce fuel imports. The delays have forced several operators to run far below installed capacity or rely on alternative, more expensive feedstock sources. While some refiners have turned to third-party suppliers, others have had no choice but to suspend operations altogether.

Industry experts attribute the limited output of modular refineries to a combination of structural and operational constraints. The Vice Chairman of the Crude Oil Refinery-owners Association of Nigeria (CORAN), Mrs. Oludolapo Okulaja, identified key challenges including poor infrastructure, unreliable power supply, weak transportation networks, and inadequate or non-existent pipeline infrastructure—all of which significantly raise operating costs. Although policy incentives such as duty waivers on imported equipment and tax reliefs exist, Okulaja argued that implementation remains inconsistent. “These incentives need to be properly executed within a clear and workable framework that beneficiaries can actually access,” she said.

Echoing these concerns, CORAN’s National Publicity Secretary, Eche Idoko, revealed that modular refineries have yet to receive a single barrel of crude from NNPC Ltd. since the naira-for-crude initiative commenced in October 2024. “As a result, most modular refineries are operating at about 20 per cent capacity,” Idoko said. “They are forced to source feedstock from third parties, which is usually very expensive.” He added that Edo Refinery, for example, relies on trucked crude from third-party suppliers, driving landing costs to nearly four times what they should be. Waltersmith and Aradel refineries, he noted, are able to operate only because they source crude from their own marginal fields—though even that supply is insufficient to fully meet plant requirements.

The naira-for-crude scheme was designed to address precisely these constraints by allowing local refineries to purchase crude oil in naira through NNPC Ltd. Under the arrangement, NNPC says it has supplied about 48 million barrels of crude to the Dangote Refinery. Although the original plan envisaged supplying seven smaller refineries alongside Dangote, only the Dangote facility ultimately benefited—and even it did not receive the full volumes initially agreed.

Okulaja said the situation has become critical. “Both modular refineries and the Dangote Refinery are in urgent need of consistent feedstock. Supplying crude to local refineries should now be a top government priority, so plants can operate at optimal capacity,” she said.

She cited cases where refineries with installed capacities of 10,000 barrels per day—equivalent to 300,000 barrels per month—are allocated as little as 30,000 barrels for an entire month. “That simply does not make sense,” she said. According to Okulaja, local refiners have the potential to transform Nigeria into a net exporter of high-quality petroleum products while simultaneously meeting domestic energy needs. Achieving this, however, requires deliberate policies to expand refining capacity and prioritise in-country value addition. “Refining our crude locally creates far more value than exporting it as raw material, only to import finished products at higher prices and often inferior quality,” she argued.

She identified regulatory bottlenecks, limited access to financing, and inadequate domestic crude supply as the most pressing challenges. In particular, she accused the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) of failing to fully enforce the Domestic Crude Oil Supply Obligations (DCOS) framework, thereby depriving both modular refineries and the Dangote Refinery of reliable feedstock. Okulaja also pointed to Nigeria’s persistently low crude oil production, attributing it partly to theft and vandalism. “Despite decades of oil production, Nigeria has not translated its resources into meaningful national development or wealth,” she said. “The continued reliance on imported, often substandard, petroleum products reflects a failure to adequately support domestic refining.”

Demand versus supply security

Given the sheer scale of the Dangote Refinery, many analysts argue that Nigeria should, in theory, have ended petrol importation. Aliko Dangote has repeatedly stated that his 650,000-barrel-per-day facility can meet 100 per cent of the country’s petrol demand. At about 85 per cent operating capacity, the refinery produces over 57 million litres of petrol daily, compared with national consumption of roughly 50 million litres per day. This excludes the refinery’s strategic reserve of more than one billion litres. Projections indicate that the plant could exceed domestic demand by 15 to 20 million litres daily, potentially reshaping fuel supply across Africa.

However, major marketers caution against relying on a single source for national supply. They argue that operational risks, logistics constraints, and distribution bottlenecks make sole dependence on one refinery impractical. The Executive Secretary of the Major Energies Marketers Association of Nigeria (MEMAN), Clement Isong, confirmed that all member companies currently purchase petrol from the Dangote Refinery. Nonetheless, he stressed that supply timing, logistics, and volume constraints prevent the facility from being Nigeria’s only source of petrol. “It is almost impossible for a single source to meet demand in the way marketers require it—when they want it, how they want it, and in the quantities they need,” Isong said. He explained that while some marketers require ship-to-ship deliveries, others depend on gantry loading, and queuing at a single location inevitably creates bottlenecks. According to him, these challenges have already resulted in temporary fuel shortages at some filling stations operated by major marketers.

The Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise (CPPE), however, takes a different view. The economic think-tank argues that exposing local refiners to unrestricted global competition without first addressing structural deficiencies—such as high energy costs, poor infrastructure, and limited access to finance—creates what it describes as a “policy-induced disadvantage.” To ensure that protective measures deliver long-term benefits, CPPE recommends complementary interventions, including low-cost financing, reliable power supply, infrastructure investment, and streamlined regulation. “Protection must be strategic, time-bound, and performance-based,” the group advised, adding that once domestic refineries achieve stability, Nigeria should pivot toward export competitiveness. The centre also called for robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks to ensure that protection drives productivity, innovation, and price moderation, rather than rent-seeking or inefficiency.

…Culled from The Nation

-

Art & Life9 years ago

Art & Life9 years agoThese ’90s fashion trends are making a comeback in 2017

-

Entertainment9 years ago

Entertainment9 years agoThe final 6 ‘Game of Thrones’ episodes might feel like a full season

-

Business9 years ago

Business9 years agoThe 9 worst mistakes you can ever make at work

-

Art & Life9 years ago

Art & Life9 years agoAccording to Dior Couture, this taboo fashion accessory is back

-

Entertainment9 years ago

Entertainment9 years agoThe old and New Edition cast comes together to perform

-

Sports9 years ago

Sports9 years agoPhillies’ Aaron Altherr makes mind-boggling barehanded play

-

Entertainment9 years ago

Entertainment9 years agoMod turns ‘Counter-Strike’ into a ‘Tekken’ clone with fighting chickens

-

Entertainment9 years ago

Entertainment9 years agoDisney’s live-action Aladdin finally finds its stars